I’ve been an avid user of XFCE for a very long time. I’m fond of its lightweight nature, and I feel productive in it. But when I first discovered tiling window managers, I was mind-blown. I’ve wanted to use one forever.

My first experience with one was a few years ago, before I understood how Linux window managers worked. I couldn’t yet wrap my head around the fact that you could install more than one window manager and choose what you wanted during login. I think I’ve grown since then. I faintly remember trying to install i3wm, the most famous tiling window manager at the time. I think I was taken aback by the black screen, and more so with the mouse pointer which just said X.

A year or so ago, I came across DistroTube’s Youtube Channel, where he talks about xmonad, the tiling window manager that’s written in Haskell. While I’ve been wanting to learn Haskell for a very long time, my career trajectory hasn’t afforded me the chance to learn it so far.

I’ve since moved jobs and completely shifted to Linux everywhere. I no longer want to use a non-linux machine ever again. I’m sure there’s a whole blog article about how much of a Linux person I’ve become in the past year or so, somewhere in me.

Last week, I came across dt’s video on Qtile, the tiling window manager written entirely in Python. Now that was truly enticing. I’m adept enough in Python to be able to manage complex configurations all on my own. And after skimming through the documentation, I spent a day modularizing the default qtile config since the default config gives me goosebumps, and not in a good way.

In this article, I’ll describe what I did, and how I went about it.

Installing Qtile

I decided to abstract away the entire configuration so that it doesn’t live in my dotfiles repository. I wanted to create a python library for myself so that it would have a bunch of utilities for my own consumption.

Additionally, I disagreed with the default way of installing Qtile. As a principle, I never sudo pip install anything. Instead, I asked my friend Karthikeyan Singaravel, who is a Python core developer, and he recommended using the deadsnakes PPA for Ubuntu to install any version of Python that I chose. I tried compiling python 3.10 myself, installing to /opt/qtile/ using configure --prefix /opt/qtile/ during the configuration stage of the source code. However, I admit that using deadsnakes is a far better idea since I could create a virtual environment based on python3.10 into /opt/qtile/ instead. I had to change the owner of the folder to my user account. Note that I could store the virtual environment in my home folder and just use that, but I wanted to isolate this outside of my home folder.

So, I installed python3.10-full and python3.10-dev (the development header files are necessary for building some of the dependencies of qtile), and I created a virtual environment using the venv module in /opt/qtile. Then, I changed the owner of the folder to my regular user account.

Then, it was time to install qtile.

Since I use the fish shell, I had to source activate /opt/qtile/bin/activate.fish to activate the virtual environment. And then I followed up by installing qtile. I didn’t pick a version right away, I decided to go with the latest version.

Qtile doesn’t setup an entry for your xsessions, so you need to do that yourself.

I created /usr/share/xsessions/qtile.desktop and filled it with the following:

|

|

Notice how I used the absolute path for qtile.

After this, I logged out of my previous window manager and switched to the new entry for Qtile.

On loading qtile for the first time, I was fairly surprised with the default config. It wasn’t as blank as i3wm and xmonad were. It had a panel, a helpful text field on the panel about how to start the launcher, and it was very easy to use. I was liking it already.

But I wanted to configure it so that I could mess with the design.

The first thing that bothered me was the lack of a wallpaper. I’d used nitrogen before, so I installed it and started it up, setting a wallpaper. I restarted qtile and then… nothing.

That was me being silly and forgetting that Explicit is better than Implicit. Like all tiling window managers, Qtile did none of the work for us. You have to ensure that the wallpaper manager loads when Qtile is done loading. That’s where the .xsessionrc file comes in.

Since nitrogen can restore a wallpaper with ease, all I needed to do was:

|

|

This went into the ~/.xsessionrc file.

Configuring Qtile

Qtile’s config file rests at ~/.config/qtile/config.py. On start, Qtile will read this file. Since this file is just Python code, that also means every single line in this file is executed.

When you look at the default config, you will notice:

- It’s about 130 lines long. Not too big.

- It’s just a bunch of variable declarations.

This meant that all you needed to configure Qtile was to ensure you set the values of a few global variables in the config file. And Qtile would take care of the rest.

This was useful. All I needed to do was set some variables.

The default config constructs all these variables as it sets them, which is something I don’t recommend. Python’s error handling will not point out the right place where the error is occurring, and while Python 3.11 seeks to improve this, it’s generally not a good practice to have a long variable declaration step in your code.

For example, where the config does this:

|

|

If you want to reuse these objects, it’s better to just construct them separately and then use them in a panel. The same goes for reusing panels.

My Current Configuration

After months of tweaking and refinement, here’s what my current Qtile setup looks like. The key principles I’ve followed are:

- Modularity: Break down complex structures into functions

- Adaptive behavior: Detect hardware and adjust accordingly

- Practical shortcuts: Keybindings that make sense for daily use

- Visual consistency: A cohesive color scheme and layout

Color Scheme and Assets

|

|

I use a consistent color palette and have custom icons for different system components. The straw hat is a personal touch - a nod to One Piece!

Smart Mouse Movement Between Monitors

One of my favorite custom functions handles multi-monitor setups elegantly:

|

|

This automatically moves the mouse cursor to the center of the next monitor when I press Super + ., making multi-monitor workflows much smoother.

Key Bindings

My keybindings follow a logical pattern:

- Super + hjkl: Vim-style window navigation

- Super + Shift + hjkl: Move windows around

- Super + Control + hjkl: Resize windows

- Super + r: Launch rofi application launcher

- Super + Shift + p: Screenshot utility

- Super + Shift + l: Lock screen

- Super + Shift + e: Power menu

|

|

Hardware-Aware Widgets

One of the most powerful aspects of a Python-based window manager is the ability to create intelligent, hardware-aware components:

|

|

These functions automatically detect hardware capabilities and adjust the interface accordingly. The battery widget only appears on laptops, and the IP address widget shows the current network status.

AMD GPU Integration

Since I run AMD hardware, I’ve integrated amdgpu_top for real-time GPU monitoring:

|

|

This provides real-time VRAM usage information directly in the status bar.

Dynamic Screen Configuration

The screen configuration automatically adapts to the number of connected monitors:

|

|

The main screen gets additional widgets like system tray and network information, while secondary screens get a simplified layout.

Startup Hooks

Qtile provides hooks for running scripts at startup:

|

|

This lets me separate one-time setup (like setting wallpapers) from things that should happen on every reload.

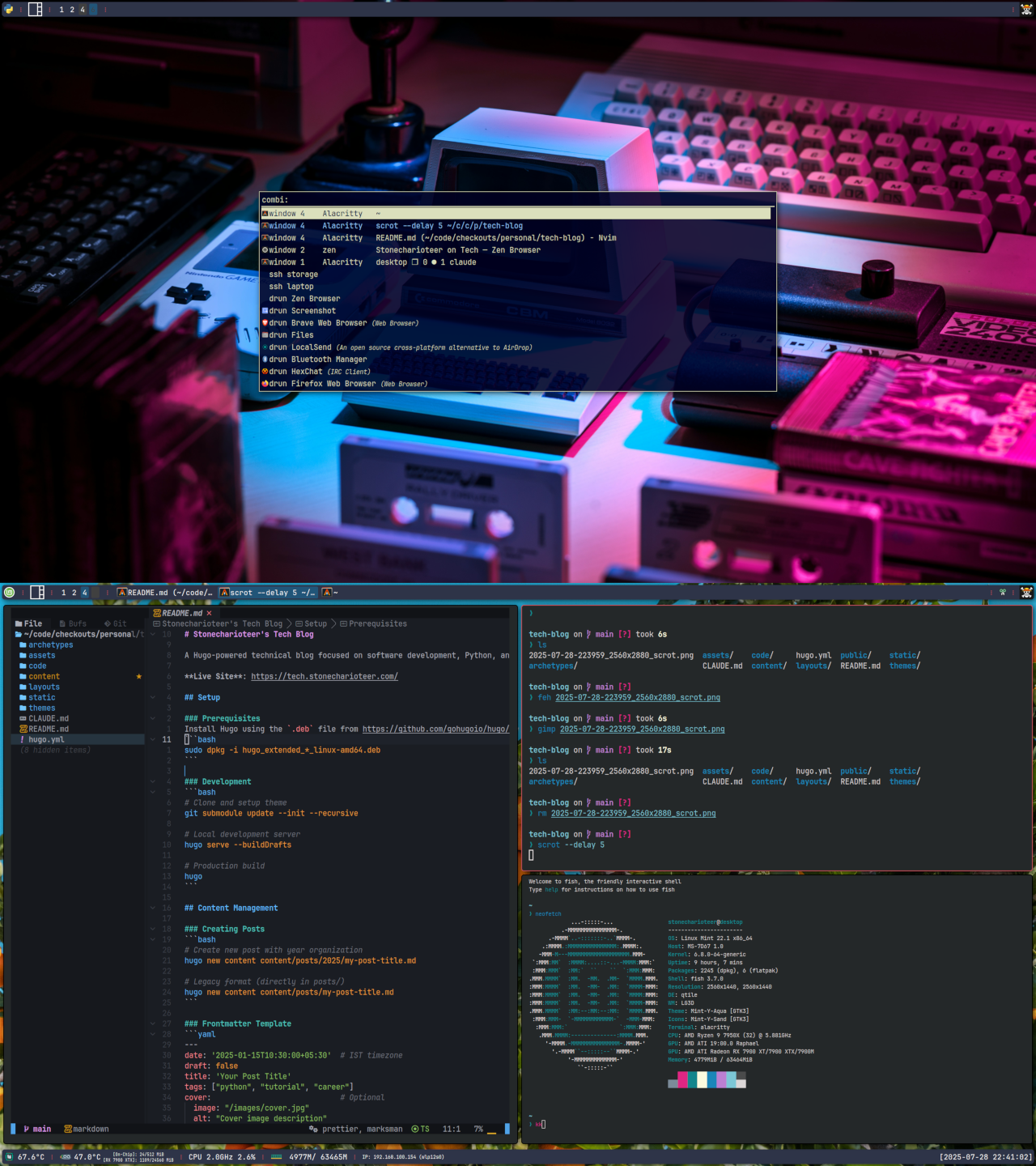

Current Setup in Action

My current setup includes:

- Top bar: Shows Linux Mint logo, current layout, groups (workspaces), task list, and system tray

- Bottom bar: CPU/GPU temperatures, VRAM usage, system resources, battery (if present), IP address, and clock

- Custom separators: Visual dividers using the “⋮” character in my accent color

- JetBrains Mono Nerd Font: For consistent icon rendering across all widgets

Lessons Learned

After using Qtile daily for months, here are the key insights:

Python Configuration is Powerful

Having your window manager configuration in Python means you can:

- Write complex logic for hardware detection

- Create reusable functions and modules

- Integrate with system tools seamlessly

- Debug configuration issues using Python tools

Start Simple, Iterate

Don’t try to recreate someone else’s rice immediately. Start with the defaults and gradually customize:

- Basic keybindings first

- Add essential widgets

- Customize colors and fonts

- Add advanced features like custom functions

Hardware Awareness Matters

Modern systems vary significantly. Your configuration should adapt to:

- Number of monitors

- Battery presence

- Available sensors

- Network interfaces

Performance Considerations

Since widgets can run arbitrary Python code, be mindful of:

- Update intervals for polling widgets

- Error handling in custom functions

- Resource usage of external commands

Future Plans

This configuration is continuously evolving. Some planned improvements:

-

Custom Widgets:

- One Piece chapter release notifications

- Gmail filtering widget

- tmux session manager

- Kubernetes context indicator

-

Better Multi-Monitor Support:

- Per-monitor wallpaper management

- Workspace binding to specific monitors

- Dynamic layout switching based on monitor configuration

-

Integration Improvements:

- NordVPN status widget

- NAS storage monitoring

- Better notification management

Preview

Here’s a look at what my config looks like today.

Conclusion

Qtile has transformed my Linux desktop experience. The ability to configure everything in Python, combined with the logical tiling approach, has made me significantly more productive. The learning curve is gentler than pure configuration-file-based window managers, and the extensibility is unmatched.

If you’re comfortable with Python and want a window manager that grows with your needs, Qtile is an excellent choice. The community is helpful, the documentation is comprehensive, and the possibilities are endless.

The configuration I’ve shared represents months of daily use and refinement. It’s not just about aesthetics (though it does look good!) - it’s about creating a workspace that adapts to your hardware, workflow, and preferences seamlessly.